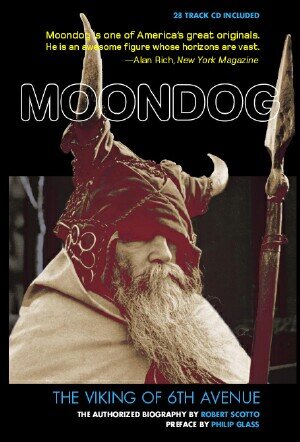

Moondog - The Viking Of 6th Avenue - Biography

Homeless, blind and dressed like a Viking, Moondog was one of New

York's

most famous eccentrics - and renowned musicians. Robert Scotto traces

the life of a legendary poet and classical composer. The book gets lots

of complaints but it is information I am after so I will be ordering

this book. Found at Amazon click here.

If you walked by the corner of 54th Street and Sixth Avenue in New

York City in the summer of 1967, the chances are you would have caught

sight of the most famous of all of the city's eccentrics. He dressed in a

Viking costume: headdress with horns, elaborate cape, spear. He was

articulate and friendly. He'd discuss the Vietnam war, the local art

scene, the grand designs of history. He would try to sell passers-by

some couplets from a mammoth work-in-progress called Thor the Nordoom.

He was blind, but refused to talk about his condition as a handicap.

Perhaps most surprising of all was that this eerie and unusual figure

was a classical composer in the tonal western tradition who followed all

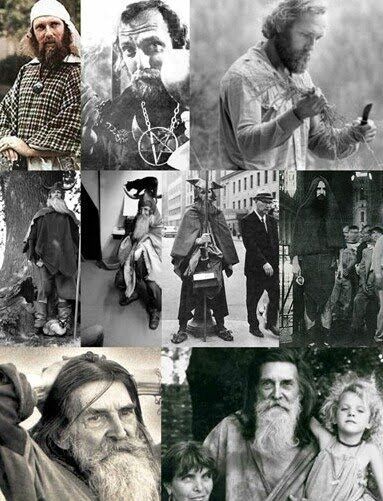

the rules of counterpoint and harmony. This man was Moondog.Moondog was a living landmark in New York, the object of pilgrimage for hippies, composers, entertainers and writers. His claims to fame are various: he is the most photographed street person in the city's history and an anti-establishment hero. One of his madrigals, "All Is Loneliness", was made into a popular song by Janis Joplin. In 1954 he challenged the disc jockey Alan Freed in court over Freed's use of "Moondog" as a brand name for the popular new genre called rock'n'roll. A serious artist, but one who approached his abilities lightly and satirically, he saw his reputation grow in strange ways until his death in Germany in 1999.

Born 83 years before in Marysville, Kansas, Louis Hardin was the son of Louis Thomas Hardin, an episcopal minister who changed parishes often. The minister's relationship with his superiors was somewhat strained, especially after he published a novel entitled Archdeacon Prettyman in Politics, a rollicking satire of religious frumpery. In order to support his family, Reverend Hardin became, over the years, a merchant, a farmer, a rancher, a postman and an insurance salesman. Young Louis's earliest memories were formed in Plymouth, Wisconsin; he grew to his teens in Wyoming. At the age of 16, in Hurley, Missouri, he was blinded for life when he was messing around with a dynamite cap, unaware of what it was, and it exploded in his face.

Louis's older sister, Ruth, read to him every day for years following the accident, and his encounters with philosophy, science and myth helped to bury whatever was left in him of his parents' Christianity. One book, The First Violin by Jessie Fothergill, inspired him to choose music as his life's work. Until then he had been interested in percussion, playing Indian drums for the high school band, but from the time he read The First Violin he was overtaken by the desire to be a composer. His father may have been a poor man of the cloth, but he was also well educated and an eccentric in his own right; his library contained many books on warfare and recordings of march music.

Hardin learned Braille in St Louis, Missouri, and became proficient in several instruments at the Iowa School for the Blind. After his parents divorced, he lived in Arkansas with his father, and studied music in nearby Memphis. After his secret marriage to a socially prominent older woman was annulled by her family, he decided to head for New York with a stipend that his former wife had secured for him through a patron. With nothing but this monthly allowance in hand, he took the first of many great leaps in the dark - he was alone, with few connections, without prospects, on a bus headed to his future home.

Those who remember Louis as the Viking probably do not realise how long it took for him to arrive at his dress and his image. His "conversion" to Nordic beliefs was not an adolescent pose, but something he had long thought about, and it came in the light of harsh experience.

Music, though, was always at the centre of his life. One day, after standing by the performers' entrance to Carnegie Hall, he was "adopted" by members of the New York Philharmonic and its conductor, Artur Rodzi´nski, who treated him as a serious musician (though he eventually fell out of favour because of his dress, which was becoming more bizarre as he fashioned it himself out of squares of material sewn together). He began to compose poetry and music and to make new, original instruments to play it on. He became Moondog in 1947, when he officially identified himself with the memory of his pet, who would howl at the moon -a sound captured on one of his earliest 78rpm records, Moondog Symphony

For more than two decades, he was a musician, poet, seer, "beggar", living on the streets of Manhattan. With the exception of the first of two cross-country tours in 1948 - when he left the city to live with Native Americans out west and promote his earliest music - and the brief times he spent at his two rural retreats in New Jersey and upstate New York, he was a committed New Yorker. His self-reliance became legendary. He was, as he put it, looking for an identity, both in his lifestyle and in his music: he studied jazz, attuned himself to the city's street sounds and became a master of percussion improvisation. He sold his wares (sheet music, 78rpm records, booklets, broadsides) on the streets and began to acquire friends and a reputation.

During the 1950s, he produced a few albums, most featuring himself as the main performer: one on Woody Herman's label, Mars, three on Prestige, one on Epic, a Columbia subsidiary, and one, his arrangement of nursery rhymes, on Angel, featuring Julie Andrews at the outset of her career and Martyn Green at his nadir. On flute was Julius Baker, one of his oldest friends from the Philharmonic. Pioneers of the sound industry, such as Tony Schwartz, taped him in his street performances. The rounds and madrigals he wrote in Braille, at times painfully in the extreme damp and cold of Manhattan winters, had to be copied at great expense. His music appeared in radio and television commercials or as soundtracks for films. Gradually the public was exposed to his peculiar brand of reactionary rebellion as he appeared in concerts as well as on radio and television.

In 1969, however, his life changed dramatically, thanks to the release of Moondog by Columbia Records in its Masterworks series, backed up by an extensive promotional campaign. That year was Moondog's annus mirabilis. From being a cult figure and local treasure, he became a celebrity of a different order: an internationally famous composer of classical music who was also a unique and easily recognisable personality. The record was released soon after he moved out of Philip Glass's home, where he had spent a profitable year sharing ideas with the younger composer.

Moondog is comprised of a solid half-hour of his orchestral pieces, some dating from the late 1940s. It also features the very best of his early, larger compositions, performed by the cream of New York's musicians, definitive statements of his signature pieces: "Theme", "Bird's Lament", Good for Goodie", "Stamping Ground". It became a bestseller (though he never received any royalties) and soon passed Bernstein's Greatest Hits in the charts - a delicious triumph for Moondog, since the great maestro had never performed his music with the New York Philharmonic. He appeared on radio shows and all of the television staples, in costume, and in good form: The Today Show, The Tonight Show (where Mitch Miller surrendered his baton to him). Adverts for the record featured the Viking against the backdrop of Gotham. For a year he was courted, celebrated, vindicated: it was the closest he ever came to stardom in the US.

In 1971, Moondog 2 appeared. It was perhaps an even greater artistic accomplishment, but one burdened by too much confusion of intent and hampered by too little publicity. For two years, from 1972 to 1974, Moondog moved to Candor, New York, for an interlude of peaceful work before making another great leap.

That leap came when he fulfilled a long-delayed dream by travelling to Europe and, in so doing, returning to the site of the ancient culture that he had kept alive for so long in his clothes and his music. Except for one brief, triumphal return tour in 1989, he never returned to the US. He lived in Germany, and though it was a long way from New York City, he felt at home. The "European in exile", as he once identified himself, had returned. But, like everything else in his life, it wasn't easy: for the first year or so he lived on the streets in several German cities, not having the airfare to return to America.

In 1975 he met Frank and Ilona Goebel, whose family - appalled that such a talented and sensitive man could be left to fend for himself, blind, cold and uncared for - took him in. With their help, he soon enjoyed a working environment unlike anything he had ever known. In Germany, he wrote enormous amounts of music, including his mammoth sound saga (The Creation), more poetry (he completed Thor the Nordoom) and a variety of treatises (such as The Overtone Tree), and produced more albums than during any other period of his life.

Moondog's residence in Europe was, in every sense of the word, a triumph: he performed frequently in Austria, France and Britain (where two of his finest albums, Sax Pax and Big Band, were recorded), as well as in Germany. Domestication, he said, only improved his work. Nearly everything had changed - except the creative spark, which was as bright as it had ever been.